Neighborly Environmentalism

Why approachability, necessity, and community are the core of sustainability's adoption challenge.

Have you ever tried googling "eco-friendly house"?

Here was the first result for me:

Now, what's wrong with this picture?

No, not the fact that this looks like the cover photo for Architectural Digest for hobbits.

No, not the fact that it's a cottage-core barbie dream house built for a movie star or Bond villain with a grass fetish.

It's that--comically--there's nothing visually sustainable about this house!

Solar panels? Nope.

Heat pump? I don't know!

Electric car? Doesn't look like it.

Water recycling? There's a swimming pool, soo....

Composting? Don't think so.

Permaculture forrest? Clearly landscaped.

Energy efficient appliances? I mean... barbecue?

But this picture actually embodies a more significant hurdle to the world adopting renewable energy and sustainable products:

Relevance.

This type of marketing makes sustainability look LUXURIOUS, AESTHETIC, and SPECIAL. That's entirely irrelevant for most households in the real world.

Tragically, these products should truly be branded as the opposite:

ESSENTIAL

FUNCTIONAL

ACCESSIBLE

Most electric cars still look like sexy man-toys ripped from Tron. A lot of "eco-friendly" home goods are just aesthetic bamboo or earth-tone trinkets that a lot of people throw out after a year or two.

No wonder people are skeptical of anything marketed as environmentally friendly.

A cynical way to write this off is by saying consumerism and sustainability are incompatible. That greenwashing is just businesses adapting to higher-income segments becoming more values-oriented. And they want products to help assuage them of environmental guilt, or at least to provide the illusion of doing so!

The purist environmentalists attack this--perhaps rightly--as a culture of consumption problem. Electric cars that charge from a dirty grid or home goods that are still disposable (and cost trees, if not plastic) are marginal improvements to environmental footprint. What we need is drastic behavior change: drive less and walk more; OWN and maintain products, rather than buying new things (a piece of Patagonia's product philosophy, for example).

But in the real world, people can't easily change the way they live. There's an undeniable privilege in adopting the inconveniences of living sustainably. This means--for a lot of people--progress can only come with product or business model innovations that are compatible with people's existing lives: Sell people electric cars, while decarbonizing the grid; make it easier to fix products, recycle products, or just make things that last forever like our great grandparents did.

So that puts business back in the drivers' seat, no matter what the environmental radicals may want.

Now, how do well-intentioned businesses justify this tendency toward targeting "upmarket" segments (read: eco luxury)?

'High-end disruption'

A little buzzwordy, but it's a real innovation paradigm, coined by Clay Christensen. It describes a business that gets established selling a disruptive product to a segment with greater willingness to spend (a high price point helps the business get established, even with a sub-optimal cost structure), then improve their operations to progressively drive down the cost curve and eventually offer something affordable to the general public.

Think of computing which started with large mainframes (accessible only to institutions and businesses), eventually riding Moore's Law down to personal computing, smartphones, and so on.

Renewable energy has seen a lot of this type of innovation. Whether it's electric cars or the solar industry, the early pioneers put out an expensive product, then rode cost curves down over time. This is Tesla's approach, for example.

BUT, two critical caveats must be true, for this to be an acceptable strategy for broad-based adoption of renewables:

#1 - Business Model

The business model innovation (i.e. the technology, business operations, and/or distribution system) must be compatible with the cost reductions needed. For example, if the cost of an electric vehicle needs to be cut in half to be accessible to most people, and the cost structure of that business is 1/3rd each for technology, operations, and distribution, the business model needs to drastically reimagine TWO out of those THREE areas, in order to have a shot at accessibility. This is what Toyota did well, in traditional auto, in the 80s and 90s.

This provides a good filter for identifying "real" vs "posing" sustainability players: If they're not radically rethinking a large enough part of the cost structure of that product--it's greenwashing, and not real impact.

But "climate-positive" companies with ESSENTIAL, FUNCTIONAL, ACCESSIBLE products can't drive adoption on their own. These needs (energy, transportation, food, etc.) are too embedded in how people live their lives.

Switching demands a strong will.

#2 - A Will to Adopt

There has to be a reason to adopt the technology, once the cost comes in line with less-sustainable alternatives. Solar unambiguously saves families money in much of the United States--and has for years. And yet, not everyone who's eligible for solar financing (and has a suitable home) has panels on their roofs.

Why?

It's about gaining trust and building understanding.

People need to:

- Understand the advantage of a sustainable product over the alternative, and

- Trust the messenger enough to believe they'll get those benefits

The former is almost never solved by saying "It'll save the environment". And the latter is hard to earn unless you can PROVE the benefits to the customer by showing them other people who've achieved them. Ideally people they know, in their own neighborhoods, and with similar lifestyles.

So UNDERSTANDING and TRUST--not technology--are the true crux of sustainability's adoption challenge.

Now let's talk about how we earn those.

Build understanding by putting climate second.

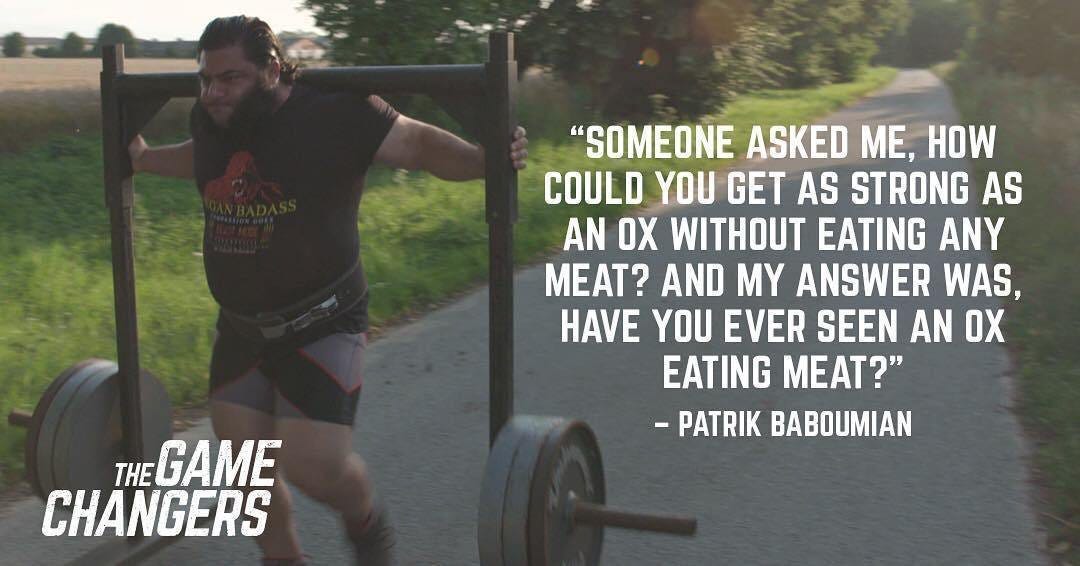

What do Arnold Schwarzenegger (bodybuilder, governor, and icon), Tom Brady (legendary quarterback), Scott Jurek (ultramarathon legend), and Patrik Baboumian (world-record holding strongman) all have in common.

Plant-based diets. AND dominant athletic careers that stretched far beyond what anyone expected.

The Game Changers was a 2018 documentary project--produced by James Cameron and athletes like Jackie Chan, Lewis Hamilton, and Novak Djokovic--interviewing dozens of athletes and nutrition scientists about the physiological and performance advantages of going plant-based.

It showed how vegetarian or vegan diets have not only improved their health, but up-leveled their performance, buffered career-ending injuries, and--for some older athletes--breathed second life into their careers.

The documentary started a movement, inspiring celebrities, athletes, and hundreds of thousands of ordinary people to embrace vegetarianism or veganism. How'd they do it?

They made climate secondary.

The film doesn't bring up the environmental impact of meat until the very end of the movie. And, even then, just for a few minutes. Their narrative motivates people through athletic feats and chiseled abs; it inspires people with stories of redemption and recovery; and it educates people through interviews with relatable experts on the actual benefits of plant based diets.

This movie successfully avoids the trip-mine of political environmentalism, a topic that--when introduced to many viewers--will trigger a distrust in the political motive of the storyteller.

A surprising analogy to this challenge also lies in entertainment: Hollywood's struggle with on-screen diversity.

For a long time, storytellers felt that audiences reacted badly to diverse characters, unless the plot of the movie focused on overcoming the adversity of identity. Audiences can feel safe watching diverse perspectives, if tokenized and simplified to a story of identity struggle. It's only recently that films like Minari (tapping a lineage from the early inclusion pioneers of Hollywood, like Star Trek!) have gotten attention by "putting identity second". They portray diversity in characters, without making diversity the core plot element.

A new generation of storytellers are teaching us that you can normalize diversity by simply letting it fall into the background.

Let's translate that to sustainability.

In today's politicized culture, the best climate storytellers (whether they be journalists, advocates, or entrepreneurs) DON'T pitch environmentalism. Instead, they...

Inspire people with potential for the future (healthier, more resilient, lower cost, etc.), rather than shaming them for lifestyles of carbon-addiction;

Focus on what makes clean products BETTER than fossil fuel alternatives, for individuals and communities

But, now that the politics are out of the way, sustainability advocates have to actually do the job of educating people on the merits of the solution (and associated lifestyle change, if any).

Building understanding usually comes in the form of handling two classic objections:

#1 - "I don't believe it'll be cheaper"

Cost is certainly the long pole in the tent when it comes to affordability. But, after all kinds of subsidies, tax credits, and rebates (thank you IRA!)--most large renewable, electric, or energy-efficient appliances are already more cost efficient than their counterparts, on a "total cost of ownership" basis.

The problem is communication.

Although many structures exist to communicate savings of going green (e.g. solar savings calculators, electric vehicle cost of ownership calculations , or energy efficiency rebate guides) most involve complicated financial calculations that aren't intuitive for most average Americans. Most actually involve math beyond the reach of the one third of the country that IS college educated!

It's hard math and, when it's being told to you by a salesperson, you're even less likely to trust the result.

#2 - "I don't believe the technology/ecosystem is mature enough"

Some people get range anxiety with EVs, despite not doing more than one real road trip per year. Some people worry about how their heat pump will perform in a cold snap, or whether they can find a service tech who knows how to work with them.

Sometimes those concerns are well founded. Maybe a town has no EV chargers, or no HVAC technicians who know heat pumps well. But infrastructure will only be built in response to demand signals, not the other way around. Building fast chargers in rural Kentucky won't make Teslas pop out of the ground. It's a bit of a chicken and egg issue: you need to jumpstart both at the same time.

But even if these ecosystem concerns AREN'T well founded, there's usually still hesitation. No matter how many EV charger maps or heat pump spec sheets you show a customer--they'll likely still have a fear of making the jump. Because they don't know what they don't know.

The only way to get anyone to take a leap of faith is the reassurance--not of a salesperson--but of a peer. Ideally a neighbor. And especially for products that have complex savings calculations, and poor communication (as discussed above)--you need TRUST.

The secret is that trust underpins understanding, which lead to adoption. And the most trusted path for anything (lifestyle, hobbies, hiring...) has always been the same thing:

Community, locality, and word of mouth.

Earn trust by being neighborly.

Think of it this way.

What's the difference in choice that a consumer must make, when considering “going green”, if they live in Portland, Oregon vs Albuquerque, New Mexico?

Let's see...

Different amounts of sunshine, affecting solar yields

Different net metering policies, affecting savings you get from going solar

Different utility districts affecting cost of energy, and electrification rebates

Different degree and modes of public transportation, affecting how much (and how far) people drive

Different amounts of EV charging infrastructure

Different high/low temperature ranges (and humidity levels!), affecting suitable HVAC appliances for temperature control

Different real estate markets, affecting what types of improvements people put into their homes

Different degrees of water scarcity, affecting water infrastructure and availability of collection products

Different availability of farm land, affecting how easy it is to buy local produce

Different building codes guiding standards and use of construction materials and energy efficient appliances

Different levels of education, affecting awareness about nutritional impact of processed foods or chemical contamination of produce

Different degrees of local industry or artisans, affecting how easy it is to buy local goods

Different cultures and recreational activities, affecting people's energy and consumption patterns

Different median incomes, affecting price sensitivity to adopting any of the above behaviors

Different priority issues for local governments, utilities, public utility commissions, regulators, etc.

So in short... just about everything.

When it comes to essential goods--power, heating, transportation, food, water--location governs so much about our consumptions habits because it steers our choices and incentives.

In contrast, one of the biggest precepts of consumerism is that you can convince people to buy anything, no matter where they live. Books on Marketing--including famous ones like The Tipping Point or You May Also Like--could fill up entire libraries. Companies like Alphabet, Meta, and Amazon have built some of the largest businesses on earth by harnessing the power of advertising or product recommendations.

But the consumerist mindset is coercive. It's what gets us the "eco-friendly", hobbit-porn home above:

LUXURIOUS

AESTHETIC

SPECIAL

Instead of what sustainable products should actually be:

ESSENTIAL

FUNCTIONAL

ACCESSIBLE (mundane, even!)

In reality, these product categories should be seen as "needs", not "wants". They are essential services, which is what local government and communities are LITERALLY designed to facilitate.

As Gaia Vince explains in Nomad Century, city-states dominated politics well into the industrial revolution. The English and the French didn't even speak common national languages, respectively, until the end of the 19th century! It was only the need for provisioning industrial resources (e.g. coal, steel--that couldn't be supplied in most places locally) that gave the nation-state any governing purpose beyond the military.

So what does a locally-driven movement look like, in adopting sustainable paths to these essential goods?

It could be advocacy groups like the CCL that table at farmers markets to educate neighbors on the benefits (and risks!) of adopting renewable energy products, in their area. They also organize "Work Parties" to get people to support voter turnout for local initiatives around building electrification.

It could be local governments partnering with utilities and public utility commissions to offer the right incentive programs (e.g. rebates, net metering policies) that save people money and support infrastructure resilience.

It could be businesses that partner with local governments to offer great terms on their energy products. My old company, PosiGen, paved the way here through innovative city partnerships as well as state-level ones helping bring federal climate funding to specific communities.

The attendees, participants, advocates, businessfolk, politicians and beneficiaries involved in these examples may range across the political spectrum. They're unified in local identity and a concern for their community.

It's not environmental activism, it's basic public services.

It's how we get neighbors to put down political blinders, and build trust.

It's how we get households to try something that will save them money and make their lives better (NOT because it saves the environment).

It's how we get utilities to support net metering, and incentivize energy efficiency.

It's how we get local governments to adapt building codes to support electrification.

It's how we get farming associations to build marketplaces for natural fertilizer, and take a jump into regenerative agriculture.

And it's this philosophy which gives us a playbook to approach sustainability challenges (and draw inspiration from solutions) anywhere in the world, vs patronizing top-down approaches.

This is big tent environmentalism--NEIGHBORLY environmentalism.

And you'd be amazed how many people you can fit in the tent, if you leave the soapboxes outside.

Wow, there's a lot to digest here Jordan. The order in which you've written leads both the naysayers and the supporters how to feel more comfortable in these key tense areas of debate or trolling, unfortunately. Biggest takeaway, stay focused on the benefits and continue to engage.