Fossil Leapfrogging

Why studying developing countries will teach us how to democratize sustainability

Flying into Kathmandu on a clear day, you'll look out the window and see the snow-capped peaks of the Langtang mountains. You'll look down to see an expansive valley--an urban sprawl of three-story homes, colored in pastel pinks and blues, covered in green blotches of farms and fruit trees.

The closer you look at the buildings, however, you'll start seeing tiny black squares sprinkled on most of the rooftops:

Solar panels? Not exactly!

They're solar hot water systems!

For those of us in the west who heat our water with dinosaur goop, this may seem like a bizarre contraption, but it's very simple. These little rigs of thermal genius use the sun to heat water as it flows through borosilicate glass tubes, then deposits the water into an insulated tank. In developing countries, these systems can save up to 80% of a household's energy cost, since water heating demands so much power.

So how does a poor country like Nepal, ranked 141st (out of 179!) in GDP per capita, afford sustainability technology that hasn't even become mainstream in the US?

Need.

The need for these tools comes down to the savings and resiliency benefits that families in the region require. And this value proposition is at the heart of developing countries' sustainability journeys.

Sustainability as Survival

Developing countries are a sustainability paradox.

On the one side, you have the open burning of trash, dumps the size of mountains, coal and dung cookstoves (often indoors!), litter-strewn countrysides, and polluted cities. A classic diagnosis of these issues will boil down to poor governance, waste management, education, and--more critically--other more urgent priorities like not dying of hunger, thirst, cold, disease, war, etc... Very understandable. And in the face of these challenges, many western onlookers can get overwhelmed by the heart-stopping enormity of these problems.

But on the other hand, corners of these economies and cultures shine as bastions of sustainable thinking. By the mid 2010s, China had 70% of the world's total solar thermal capacity (e.g. solar hot water). Electric three-wheeler (like tuktuks!) penetration in India is currently estimated as high as 45% (with scooters coming up fast behind). In Nepal, over 72% of the population of the country grows their own vegetables.

Do they adopt these practices because of sustainable thinking? Maybe some do. But, having talked to homeowners, tuktuk drivers, and farmers in these countries, the real reason is simple: survival.

Energy is expensive when you don't have money. Solar hot water has $0 marginal cost. Tuktuk drivers sitting in traffic all day will have their earnings evaporate if they spend all their money on gas. Households who can't afford imported fresh produce (transportation = energy = cost) have to farm for themselves, whenever possible.

Why should we--in rich countries--care about this? We don't face these same challenges, constraints, and scarcities.

The first reason is obvious: we all live on the same polluted blue marble. We have a vested interest in these countries being successful, and so have a duty to help (and therefore first to understand their challenges to see HOW we can help).

But the second reason is key. EVERYONE, in all countries, needs to reduce their ecological footprint as much as possible. But most people, sadly, can't palate drastic lifestyle changes. So we need innovations to provide the same quality good or service, with a lower footprint. The only issue is that these innovations usually come at a higher cost, and become somewhat of a luxury good. We call this effect the Green Premium--it's visible in everything from the cost of meat alternatives to renewable energy to low-carbon cement.

But broad-based emissions reduction can only happen if everyone can access these new tools--not just wealthy individuals or companies.

Now, who do you think can come up with a more clever and accessible sustainability innovation: the western entrepreneur working in an ecosystem that sees sustainability as a "nice to have", or the developing country entrepreneur building "MUST have" solutions to help people literally survive?

I'd pick door number two. Desperation is a powerful force for innovation.

That's not to say rich countries can't develop powerful "must have" sustainability products--PosiGen, for example, is a nationwide solar and energy efficiency provider that offers life-changing savings to low- and moderate-income Americans.

But here's the truth: developing economies will prove to be more fertile soil for accessibility-first sustainability technologies to emerge. And what's more, they don't have nearly as much shackling them to the old system. That's a powerful recipe for innovation--one we can ALL learn from.

The Leapfrogging Opportunity

Most developing countries find themselves at a sustainability crossroads.

With less physical (and behavioral) fossil infrastructure than in the West, they're facing an unprecedented leapfrogging opportunity, with less entrenched industry, lobbying, and political power to resist change. The tools they forge may become the paths of least resistance for the new energy economy--and they're likely going to prove useful in our own backyards too. Whatever they do, however they do it, we need to be taking notes.

But energy leapfrogging won't be an easy task. These countries face two critical barriers:

Decarbonizing the grid to produce clean electrons

Decarbonizing lifestyles by improving access to the appliances and vehicles that run on those electrons

1: Clean Electrons

Any path to reduced fossil dependence relies on the electrification of everything. Decarbonizing grids in developing economies means a few things.

First is making utility-scale renewable energy the lowest cost electron, in order to phase coal, oil, and gas plants out of the grid. This challenge is similar in countries everywhere and are merely a function of energy generation costs (commonly referred to by a metric called the "Levelized Cost of Electricity", or LCOE), which we know tipped in favor of renewables in 2018.

Check.

Second is the adoption of distributed generation (i.e. rooftop solar and batteries) for the resiliency and load management needs of an electrifying economy. Clean generation from solar and wind farms can't power homes if the infrastructure can't support the increased load. Meanwhile, existing transmission and distribution infrastructure is already under tremendous stress and likely won't be able to handle the added load of electrified transportation, heating/cooling, cooking... without some help.

Luckily, rooftop solar has a bright future in developing economies, despite the small roof sizes. The reason is savings (it always is!). In India, for example, energy costs are tiered, but average ~6 INR/kWh. A typical 1kW solar system costs ~60,000 INR. At 1400 kWh per year of production, that's 8400 INR savings per year, and a payback just after 7 years! Not bad. And even if you don't assume a sell-back structure with utilities, battery adoption can be surprisingly high in developing economies due to power intermittency, making this transition easier. New business models are emerging every day to tackle these electrification and grid resilience challenges, such as swappable EV batteries, for another Indian example.

Check.

The last piece of the puzzle is rural energy decarbonization. Developing countries countries have lower urbanization rates--the US is at a startling 83% while India is only at 35%, for example. They'll need to find ways for remote communities to use renewable power and, luckily, distributed generation is perfectly suited to this use case. Water and sunlight don't need to be transported by truck or power lines, and they are still the resiliency electron of choice in the most rugged and remote terrains.

Check.

2: Accessible Electrification

The technologies to support electrified life already exist: electric vehicles, heat pumps, induction cooking surfaces, solar hot water, etc. But adoption will stall without accessibility, which has two accelerants:

Financing: getting access to the product without prohibitively large upfront sums

Savings: ensuring the cost of ownership is unambiguously less (so there's immediate savings from buying the appliances)

Financing is important because upfront payments don't make sense in developing countries (and aren't preferred even in rich ones!). Low incomes and low savings make lump sum payments a non-starter. So you need some type of payment plan. Luckily, developing countries have already made tremendous strides in consumer credit, driven by the boom of "digital credit" companies over the last 15 years. The global "buy now pay later" (or "BNPL") industry, despite serious challenges, is still growing at a rate of ~48% year over year.

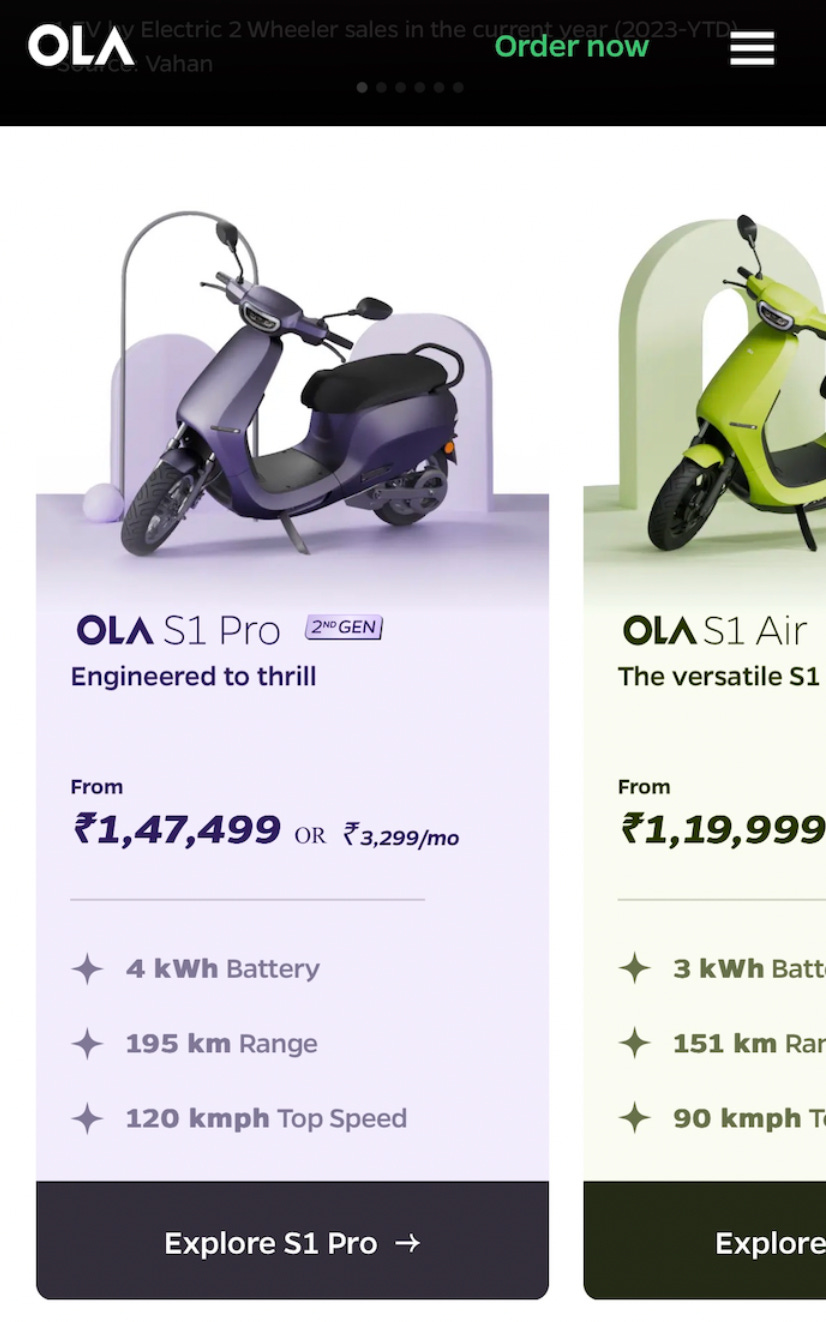

Today, you can start seeing financing for electric products everywhere you look. Ola, the Indian ride-hailing super-app, has an electric ride tab which launches electric bike financing promotions as soon as you tap it.

The second piece of accessibility is savings. A payment plan for a new appliance still won't drive adoption if there isn't proof that it will save money--these buyers are highly savings-conscious. But the good news is that going electric does save money. As mentioned above, EVs save on expensive gas, solar hot water saves on expensive electricity, home hardens save on expensive produce.

Education is the final piece of accessibility, since it's needed to understand consumer lending products and savings opportunities. Although formal education often leaves much to be desired, anyone who's spent meaningful time in developing countries can vouch that these consumers are as financially shrewd as they are frugal, when it comes to lifestyle choices that maximize savings and independence.

Sharing the Wealth

The west has coupled growth and living standards with fossil fuel consumption. Developing countries, meanwhile, find themselves in a position to decouple this growth. They can leapfrog several layers of fossil infrastructure, as they acquire new appliances to boost their standards of living (things like air conditioning!) that can be electric from the get-go. In doing so, they'll leverage cultures of frugal innovation, also called "Jugaad", to create models that will show the whole world how to improve our own resource efficiency, and how to democratize access to sustainability products.

But it's not a free show; it needs to be a two-way street. Rich countries have been instrumental in pioneering renewable technologies, and using our deployments to create markets for components and services, build cohorts of technicians and specialists, and drive down costs across the board. That momentum needs to continue. But we also need to do more. Developed market startups should partner with developing clean innovators to boost their credibility and exposure, while transferring knowledge. Rich countries' investors and asset allocators should be more active in these markets. Financial institutions and credit risk underwriters should parlay their renewable technology expertise into new financing products for the rest of the world. Rich governments should collaborate on workforce development, education, and incubation programs.

To be clear--these types of partnerships are not charity. Our startups would gain resiliency from learning new business models and winning potential footholds in new markets. Our investors and allocators would earn higher returns in these growing geographies. Our financial institutions and lenders would expand market share and broaden their loan portfolios. Our governments would strengthen economic alliances.

Addressing climate change requires these two worlds to work in a sustainability symbiosis.

We need to rebrand sustainable development not as programmatic hand-outs, but as a rare opportunity to learn resource efficiency from the world's most talented at resource efficiency.

That's the ultimate goal of this blog, in fact. Not some kind of educational sustainability or poverty tourism, but a exploration of what that symbiosis looks like and the role we can play within it.

Legend has it that Kathmandu valley used to be a lake. A vile and snake-infested backwater. One day a beautiful lotus flower fell onto the lake, and a powerful Boddhisatva--looking to hold the flower--cut a gorge in the mountains and drained the water, uncovering the valley that now thrives as the urban jewel of the Himalayas.

The lotus flower, known to bloom immaculately from mud, represents purity, resilience, and rebirth. That Boddhisatva was named Manjushri--the Boddhisatva of knowledge.

It's clear that places like Kathmandu have a lot of knowledge to impart. And if we listen, that sustainable, resilient, and pure economy we so desperately need may just be reborn.